Memphis was both an old city and a new city when the war began. Native Americans, like the Chickasaw and their ancestors, had inhabited the area for centuries. Settlers had built some homes on Fourth Bluff prior to October 1818, when the Chickasaw elders sold more than six million acres of land to the United States. Shelby County, named for Revolutionary War hero and Kentucky governor Col. Isaac Shelby, was established by the Tennessee General Assembly in November 1819. By the time Tennessee left the Union in 1861, Memphis was major port on the Mississippi River. Shelby County had a population of 48,092 people, which included 276 free people of color and 16,953 slaves. This included “bankers and manufacturers, cotton buyers and factors, wholesale grocers and slave traders, doctors and lawyers, editors and railroad presidents.” 22,623 people lived in Memphis alone, making it the thirty-eighth largest city in the United States. Memphis had a fire department, hospital, and city streets paved with cobblestones.[1]

|

| Memphis, ca.1862, LOC |

When the vote for United

States president came in 1860, the men of Memphis cast 2,319 votes for Stephen

Douglas, 2,250 votes for John Bell, and a mere 572 ballots for Vice President

John C. Breckinridge. The men of Memphis were more inclined at this stage to conditionally

support the Union. With the secession of South Carolina in December 1860, the

tone of the people in Memphis slowly began to change. Both pro-Union and

Secession meetings were held across the city. With the Federal resupply and subsequent

Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, followed by Lincoln’s call for volunteers to

suppress the rebellion, more and more Memphis citizens supported secession. Tennessee

Governor Isham G. Harris called for a meeting of the legislature in Nashville.

On May 6, the General Assembly passed a Declaration of Independence. The

following day, Harris agreed to a military allegiance between Tennessee and the

Confederate government. These actions were ratified by a public vote on June 8.

Memphis, its port,

the most important port in Tennessee, and even more importantly, the railroads,

quickly entered the discussion. In August 1861, Confederate Rep. David M.

Currin requested $160,000 “for the construction, equipment, and armament of two

ironclad gunboats for the defense of the Mississippi River and the city of

Memphis.” The bill was signed into law the next day.[2]

Prior to the war, from 1844 to 1854, Memphis had a US Naval dock. Several

private shipyards still existed along the Mississippi River. Two twin-screw

vessels, the Arkansas and the Tennessee, were contracted to John

T. Shirley, a local Memphis businessman. He was to deliver the two vessels by

December 1861, at a cost of $76,920 each. The ships were to be 165 feet in

length, and a draft of no more than 8 feet when loaded. Shirley struggled to

find skilled carpenters and shipwrights, and both he and Secretary of the Navy

Stephen Mallory implored district commander Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk for details

of men to help with building the ships. Not having enough experienced hands,

Shirley concentrated on building the Arkansas. Lieutenant Henry Kennedy

Stevens arrived from Charleston, assigned as the executive officer of the Arkansas,

and took charge of the operations.[3]

Memphis appeared in

the campaign plans of several Federal commanders, including George B. McClellan,

David G. Farragut, and Abraham Lincoln. McClellan’s tenure as general-in-chief

was short lived, although he did approve of a plan of taking New Orleans first,

followed by Baton Rouge, the railroad hub at Jackson, Mississippi, and then

Mobile, before setting his sights on Memphis. Farragut, a “firm advocate of combined operations,”

submitted a plan to force the Confederates out of their defenses around New

Orleans, then proceed up the Mississippi River, taking Baton Rouge, Vicksburg,

and then Memphis. After firing McClellan, Lincoln’s strategy was “a joint

movement from Cairo to Memphis; and from Cincinnati to East Tennessee.”[4]

Fort Henry, Fort Donelson,

and Nashville fell in February. Governor Harris ordered the General Assembly to

convene in Memphis on February 20. Island No. 10 fell in April 1862. Only Fort

Pillow remained to protect Memphis. Mallory ordered the Arkansas to New

Orleans if she was in danger of capture. To the west, the Confederates lost the

battle of Shiloh on April 7, and to the south, the bombardment of New Orleans

began on April 18. Four of the Southern flotilla from Fort Pillow made their

way to Memphis after the fort was abandoned on May 10, 1862. The Federals knew of

the construction of the ironclads at Memphis, and Farragut worried that just

one of them could destroy most of his ships and maybe even retake New Orleans. Farragut

would not get a crack at Memphis.[5]

Braxton Bragg

ordered the evacuation of Memphis, and by June 4, the earthworks constructed on

the river were empty. Only the small naval flotilla remained. On June 6,

Federal Commander Charles Davis, with five ironclads and four rams, headed

toward Memphis. The Confederate fleet, eight vessels mounting twenty-eight

guns, under Capt. Joseph E. Montgomery, was the only force between the Federals

and city. In the two-hour-long fight, only one of the Confederate gunboats escaped:

the General Van Dorn. Three Confederate vessels were destroyed, and four

others fell into Union hands. The Arkansas had been towed up the

Yazoo River a month before the battle of Memphis. Historian William N. Still,

Jr., believes that had the Arkansas been left in Memphis, she might have

been finished in time to take part in the battle. The Tennessee was

destroyed the night before the battle of Memphis.[6]

Mayor Parks

surrendered Memphis, and the city was occupied by Col. G.N. Fitch and a brigade

of Indiana Infantry. The civic leaders had to swear an oath of allegiance to

the Union, and martial law was declared on June 13. Maj. Gen. U.S. Grant was in

Memphis by June 23, finding the city in “bad order” and “secessionists

governing much in their own way.”

Elections were held, and voters were required to swear the Oath of Allegiance

before they could vote; property of pro-Confederate sympathizers was seized to

pay for acts of destruction caused by partisans; partisans were “not entitled

to the treatment of prisoners of war when caught”; it became a crime to display

Confederate symbols; and, men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five had

to take the oath or leave the city. Because Memphis was firmly under Federal

control, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the city.[7]

With local

businesses refusing to open, hundreds of merchants from Cincinnati and

Louisville arrived with goods, opening new stores. With open roads, this

allowed goods to flow into Confederate hands. One observer believed that more

than $20 million worth of supplies left Memphis, bound for the Confederate

army, during the war. Confederate forces skirmished with their Federal

counterparts in Shelby County frequently. Memphis became a major supply depot for the

Federals operating in western Tennessee, northern Mississippi and Alabama. Numerous

raids and large-scale operations, both on the Mississippi River and overland,

set out from Memphis. The Federals often retreated to the defenses of the city

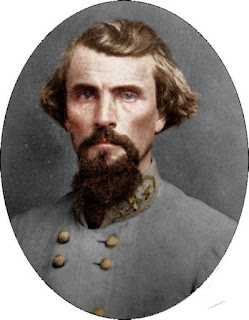

after confrontations with Confederate commander Nathan Bedford Forrest.[8]

There was some

discussion by the Confederate high command of recapturing the city. In October

1862, Jefferson Davis wrote to Maj. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes with plans to

unite Southern forces in the west and drive the Federals out of the area, recapturing

Helena, Memphis, and then Nashville.[9]

Nothing came of the idea, but on August 21, 1864, Nathan Bedford Forrest rode

into Memphis with 1,500 men and two cannons. “I attacked Memphis at four o’clock

this morning, driving the enemy to his fortifications,” Forrest wrote later

that day. “We killed and captured four hundred, taking their entire camp, with

about three hundred horses and mules. Washburn and staff escaped in the

darkness of the early morning, Washburn leaving his clothes behind.”[10]

“Memphis Captured by Forrest” ran several Northern newspaper headlines. While Forrest

failed to capture the three Federal generals in the city and only held the city

for a few hours, he did divert the attention and draw resources away from other

theaters of the war.[11]

|

| General Washburn leaving his clothes behind. |

While Memphis was spared the fate of other Southern cities like Atlanta, Columbia, and Richmond, it had one final role to play for history. On April 27, 1865, the boilers on the S.S. Sultana, carrying over 2,200 former Federal prisoners from Andersonville and Cahaba, exploded in the Mississippi River just north of Memphis. It is believed that 1,195 of the 2,200 passengers and crew perished in the explosion and subsequent fire. The loss of the Sultana was the deadliest maritime disaster in United States history. Many of the victims are buried in the Memphis National Cemetery.

While every other Southern city with a

population of over 20,000 people has a history of its wartime years(and in some

case, multiple published histories), Memphis apparently does not.

[1] Dowdy,

A Brief History of Memphis, 13-24.

[2] Still,

Iron Afloat, 16.

[3] Luraghi,

A History of the Confederate Navy, 107, 119, 129.

[4] Reed,

Combined Operations in the Civil War, 61-62, 66.

[5] Reed,

Combined Operations in the Civil War, 198.

[6] Luraghi,

A History of the Confederate Navy, 169; Still, Iron Afloat, 62.

[7] Dowdy,

A Brief History of Memphis, 13-24.

[8] Dowdy,

A Brief History of Memphis, 13-24; Long, Civil War Day-by-Day.

[9] Papers

of Jefferson Davis, 8:454-56.

[10] Wyeth,

That Devil Forrest, 417.

[11] Daily

Ohio Statesman, August 25, 1864; The Times-Democrat, August 28,

1864; New York Daily Herald, August 29, 1864.