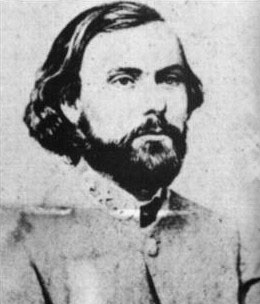

Brig. Gen. John W.

Frazer was in an awkward position. As Braxton Bragg stripped Confederate forces

from east Tennessee to strengthen the Army of Tennessee prior to attacking the

Federals around Chattanooga, Frazer’s brigade, posted at Cumberland Gap, was

left behind. Frazer was a native of Hardin County, Tennessee, and received an appointment

from Mississippi to the United States Military Academy, graduating in 1849. He

performed garrison duty in New York, California, Virginia, and Washington State

before resigning and joining the Confederate States army. He was commissioned lieutenant

colonel of the 8th Alabama Infantry, and then colonel of the 28th

Alabama Infantry. On May 19, 1863, he was appointed brigadier general and

assigned to command the 5th brigade, Army of East Tennessee. His

command, composed of the 55th Georgia Infantry, the 62nd

and 64th North Carolina Troops, the 64th Virginia

Infantry, and the 1st Tennessee Cavalry regiment, was assigned to

guard various gaps in and around Cumberland Gap.[1] Brig. Gen. John W. Frazer

Simon Buckner,

Frazer’s immediate commander, wrote on August 21, asking Frazer if he needed

ammunition or other supplies. “Matters do not look gloomy,” the letter stated. Toward

the end of August, it appears that Frazer was getting ready to evacuate

Cumberland Gap. But that same day,

August 30, Buckner ordered Frazer to “hold the gap…” and if he evacuated

Cumberland Gap, to fall back to Abington. With Buckner gone, Major General

Samuel Jones assumed commander of the department. From surviving

correspondence, it appears that Frazer had not taken any action on the matter,

for on September 7, Jones asked the War Department “Shall I order the

evacuation of Cumberland Gap?” James Seddon proposed to Jefferson Davis that

same question the next day: “Shall I authorize the gap to be held?” Davis,

wanting to “save the railroad and the valuable position at Cumberland Gap,”

allowed Jones to make that decision. Davis did not believe that the Federals in

east Tennessee, filling the void left by the redeployed Confederates, were a

serious threat.[2]

But they were. Bypassing

the Confederate stronghold at Cumberland Gap, Federal forces used a gap fifty

miles southwest of the area. The attacking Federal force in East Tennessee was

under the command of Major General Ambrose Burnside. He sent one brigade to

approach Cumberland Gap from the south, while another Federal brigade was

slated to move south from Crab Orchard along the old Wilderness Road toward

Cumberland Gap. The two Federal forces appeared about the same time on opposite

sides of Cumberland Gap. On September 7 came the first demand to surrender, a

demand that Frazer rejected. Under the cover of darkness the Federals burned

the mill Frazer was using to grind corn for his command, along with some of the

meal. The next morning came another demand for surrender. While Frazer weighed

his options, another demand of surrender was received, this one from Burnside,

who had just taken Knoxville. At 3 o’clock on September 9, Frazer surrendered

his entire force, except about four hundred men who had slipped off into the

woods.[3]

Frazer’s surrender

to a smaller force was not without controversy. He was rumored to be drunk. “Two

thousand men and guns & ammunition have also been given away at Cumberland

Gap, where a drunken Brigadier named Frazer commanded,” Josiah Gorgas wrote in

his diary on September 17, 1863.[4]

War Department Clerk J. B. Jones wrote that the “country is indignant at the

surrender of Cumberland Gap by Brig.-Gen. Frazier, without firing a gun, when

his force was nearly as strong as Burnside’s. . . The country did not know

there was such a general until his name became famous by this ignominious surrender.

Where did Gen. Cooper find him?”[5]

Frazer apparently did not consult the officers of the regiments in his command

on September 9. He surrendered between 1,700 and 2,300 men, and most of those

men were sent to Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois. Many of these men died of

illness. Frazer was criticized by Jefferson Davis, and in February 1864, the

Confederate senate voted unanimously against confirming his nomination as a

brigadier. From Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, Frazer wrote an official report

on November 27, 1864. Frazer criticized the troops under his command. They were

“in a deplorable condition.” One of his regiments, the 62nd North

Carolina Troops, the current brigade commander had been “for some time. . .

trying to get rid of it.” Frazer considered this regiment “badly disciplined

and badly drilled” One captain was under arrest for “disseminating papers

hostile to the Confederacy among the command.” The 64th North

Carolina Troops was small, “having been reduced by desertions. . . the colonel

and lieutenant colonel had left in disgrace for dishonorable conduct.” The 55th

Georgia Infantry, Frazer thought, was the best regiment he had, although the

soldiers had recently ridden their colonel on a rail. His two artillery

batteries had no experience. The “character, confidence, and condition of the

troops hastily collected to defend the gap were such as to justify no hope of a

successful defense against an equal number of the enemy. . . It is proper to

state that the want of confidence in the troops was of gradual conviction in my

mind. . .”[6]

Frazer spent the rest of the war as a prisoner. After his release in April 1865, he moved to Arkansas, and then to New York City where he died in 1906. James D. Porter, writing in 1899, believed that “when all the facts were made known,” Frazer was exonerated.[7] John W. Frazer remains one of those little-discussed Confederate generals and probably deserves more of our attention. Was he drunk while Cumberland Gap was surrounded? Maybe. The Federal colonel commanding the brigade moving from Crab Orchard thought so. Were the troops he had to work with subpar? When it comes to the 62nd and 64th North Carolina Troops, well, they were not the best the Confederacy had to offer.

[1] Davis,

The Confederate Generals, 2:146-47.

[2] Official

Records, vol. 30, pt. 4, 528, 568, 571, 572, 616.

[3] Kincaid,

The Wilderness Road, 262-73.

[4] Wiggins,

The Journals of Josiah Gorgas, 81.

[5] Robertson,

A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary, 2:43.

[6] Official

Records, vol. 30, pt.2 610-612.

[7] Evans,

Confederate Military History, 8:309.

No comments:

Post a Comment