Part of three of an infrequent series related to biographies on Confederate generals, this installment features the state of Kentucky. Other states covered include

. Like the posts on other states, this list only covers men born in Kentucky. Others who were born elsewhere but associated with Kentucky are not included on this list (such as John Hunt Morgan). This list includes only book-length biographies (and if I have missed any, please feel free to drop me a line with the title and author). There is a book, Kentuckians in Gray: Confederate Generals and Field Officers of the Bluegrass State (2008) by Bruce Allardice and Lawrence L. Hewitt that might be able to fill in a few holes.

Adams, Daniel W. (1821-1872)

Adams, William W. (1819-1888)

Beall, William N. R. (1825-1883)

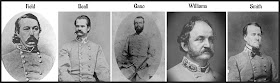

Bell, Tyree H. (1815-1902)

Hughes,

Moretti, and Browne, Brigadier General Tyree H. Bell, C.S.A. (2004)

Breckinridge, John C. (1821-1875)

Davis, Breckinridge:

Statesman, Soldier, Symbol (2010)

Heck, Proud

Kentuckian: John C. Breckinridge, 1821-1875 (1976)

Stillwell,

Born to be a Statesman: John Cabell Breckinridge (1936)

Buckner, Simon B. (123-1914)

Stickles,

Simon Bolivar Buckner: Borderland Knight (1940)

Buford, Abraham (1820-1884)

Churchill, Thomas J. (1824-1905)

Cosby, George B. (1830-1909)

Crittenden, George B. (1812-1880)

Eubank,

In the Shadow of the Patriarch: the John J. Crittenden Family in War and

Peace (2009)

Duke, Basil W. (1838-1916)

Duke, The

Civil War Reminiscences of General Basil W. Duke, C.S.A. (1911)

Matthews,

Basil Duke, CSA: The Right Man in the Right Place (2005)

Fagan, James F. (1828-1893)

Luker, Mature

Life of General James Fleming Fagan (1987)

Field, Charles W. (1828-1892)

Gano, Richard M. (1830-1913)

McLaurin,

Richard M. Gano: Physician, Solder, Clergyman (2003)

Gholson, Samuel J. (1808-1883)

Gibson, Randall L. (1832-1892)

McBride

and McLaurin, Randall Lee Gibson of Louisiana: Confederate General and New South Reformer (2007)

Grayson, John B. (1806-1861)

Hanson, Roger (1827-1863)

Hawes, James M. (1824-1889)

Helm, Benjamin H. (1831-1863)

McMurty,

Ben Hardin Helm: Rebel Brother-in-law of Abraham Lincoln (1943)

Hodge, George B. (1828-1892)

Hood, John B. (1831-1879)

Brown, John

Bell Hood: Extracting Truth from history (2012)

Coffey,

John Bell Hood and the Struggle for Atlanta (1998)

Davis, Texas

Brigadier to the Fall of Atlanta: John Bell Hood (2019)

Davis, Into

Tennessee & Failure: John Bell Hood (2020)

Dyer, The

Gallant Hood (1950)

Hood, Advance

and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States

Armies (1880)

Hood, John

Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General (2013)

Hood, The

Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood (2015)

McCurry,

John Bell Hood and the War for Southern Independence (1992)

Miller,

John Bell Hood and the Fight for Civil War Memory (2010)

O’Connor,

Hood, Cavalier General (1949)

Hughes, John T. (1817-

Jackson, Claiborne F. (1806-1862)

Johnston, Albert S. (1803-1862)

Cook, Albert

Sidney Johnston, the Texan (1987)

Johnston,

The Life of Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston (1878)

Roland,

Jefferson Davis’s Greatest General: Albert Sidney Johnston (2000)

Roland,

Albert Sidney Johnston: A Soldier of Three Republics (2001)

Lewis, Joseph H. (1824-1904)

Lyon, Hylan B. (1836-1907)

Lee, General

Hylan B. Lyon: A Kentucky Confederate and the War in the West (2019)

Marshall, Humphrey (1812-1872)

Martin, William T. (1823-1910)

Maxey, Samuel B. (1825-1895)

Horton,

Samuel Bell Maxey: A Biography (1974)

Waugh

and McWhiney, Sam Bell Maxey and the Confederate Indians (1998)

Preston, William III (1816-1887)

Sehlinger,

Kentucky’s Last Cavalier: General William Preston, (2010)

Robertson, Jerome B. (1815-1890)

Shelby, Joseph O. (1830-1897)

Bartels,

The Man who wouldn’t Surrender, even in Death: General Jo Shelby (1999)

Davis, Fallen

Guidon: The Saga of Confederate General Jo Shelby’s March to Mexico (1995)

Edwards,

Shelby and his Men: Or, the War in the West (1867)

Scott, The

Forgotten Cavalier: Confederate Raider Joseph Orville Shelby and his Great

Missouri Raid of 1862 (1900)

Slack, William Y. (1816-1862)

Smith, Gustavus W. (1821-1896)

Smith, Confederate

War Papers (1884)

Smith, The

Battle of Seven Pines (1891)

Smith, Generals

J.E. Johnston and G.T. Beauregard at the Battle of Manassas (1892)

Taylor, Richard (1826-1879)

Parrish,

Richard Taylor, Soldier Prince of Dixie (1992)

Taylor,

Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War

(1879)

Williams, John S. (1818-1898)