It is great to see another battlefield being preserved. The Goldsboro Bridge Battlefield is joining the ranks of Bentonville, Averysboro, the Bennett Place, Fort Fisher, Fort Macon, Fort Branch, and a few other sites across the state.

You can read the article from today’s Goldsboro News-Argus. I was in the area recently, and I find the events exciting. The original battle was fought on December 17, 1862, and pitted Brig. Gen. John G. Foster (US) against Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Clingman. Foster set out to destroy the Goldsboro bridge and hamper Confederate supply logistics. While the Confederates were able to delay Foster, the bridge was eventually destroyed. Casualties are estimated at 220.

Historian Michael C. Hardy's quest to understand Confederate history, from the boots up.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

On the road again.....

At times, "On the Road Again" seems to be my theme. I’ll be speaking tonight at the Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp in Greenville, NC. On Friday evening I’ll be with the Hanover Historical Society in Hanover, Virginia, and on Saturday, from 12-4, I’ll be at the Appalachian Authors’ Festival at the Carson House in Marion, NC. If you get a chance, stop by and say hi!

I’m really looking forward to the Friday trip. I’m planning on stopping at the new museum in Richmond at Tredegar.

I’m really looking forward to the Friday trip. I’m planning on stopping at the new museum in Richmond at Tredegar.

Monday, November 27, 2006

A Friday in Lenoir

This past Friday, I had a chance to spend a couple of hours with J. Timothy Cole and Bradley R. Foley, authors of a new book on Brig. Gen. Collett Leventhorpe. I’ve spent a lot of time studying Leventhorpe over the past few years, and have written a couple of articles about him and his service.

Leventhorpe was a remarkable man, born in England, well educated, and had a decade plus of service in the British Army as a captain of the 14th Regiment of Foot before coming to the United States. Once in the states, he obtained a medical degree, mined for gold, and married into a prominent family.

Once the war began, he quickly obtained the rank of colonel of the 34th North Carolina, then the 11th North Carolina (Bethel Regiment). While he held brigade level commands at various times, he was never promoted to brigadier general until the last days of the war. I feel that his backwater commands, and his wounding at Gettysburg, kept him from moving up in the ranks.

I am really looking forward to reading Cole’s and Foley’s book on Leventhorpe.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Happy Thanksgiving!

Happy Thanksgiving to everyone from the Hardys.

I’ll be doing two book signings this weekend. The first is tomorrow from 10 until 2 at the Caldwell Heritage Museum in Lenoir. The second is on Saturday at the Avery County Historical Museum in Newland, from 11 until 3.

Drop by if you get a chance.

I’ll be doing two book signings this weekend. The first is tomorrow from 10 until 2 at the Caldwell Heritage Museum in Lenoir. The second is on Saturday at the Avery County Historical Museum in Newland, from 11 until 3.

Drop by if you get a chance.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

A three hour tour...

I got to spend this past Saturday afternoon taking a small group to some local Civil War sites. We started off at the Pisgah Church Cemetery - not anyone really famous here, but one of the largest cemeteries in Avery County. From Pisgah, we went to Linville Falls. Lead was mined here during the war and shipped off the mountain. After Linville Falls, we traveled to the Bark House. It was here, or just a little south of the Bark House, depending on which historian you read, that Col. George Kirk fought his second battle on his way back from his Camp Vance raid. This was in June 1864.

Next on our adventure was the Montezuma Community Cemetery. William McKeeson "Keith" Blalock, and his wife, Sarah Malinda Pritchard "Sam" Blalock are buried here. Keith and Sam both served in the 26th North Carolina. There are other Civil War vets buried here as well - six total.

Our last stop for the afternoon was the property known as Grasslands - the home of Col. John B. Palmer during the war. Palmer moved here in 1858, and in 1864, on his way back from his Camp Vance raid, Kirk ordered, or at least sanctioned, the burning of Palmer’s house.

We talked about a couple of other sites as well - the Cranberry mines, which produced iron ore during the war. The iron ore was shipped off the mountain by wagon loads to the railroad just west of Morganton. We also discussed the underground railroad that the Blalocks helped run: an underground railroad that helped funnel escaped prisoners from Salisbury to east Tennessee. The Blalocks ran the Blowing Rock-Shull’s Mill-Banner Elk portions (then all in Watauga County) of the line.

Overall it was a great afternoon - the weather was good - a little cool, but sunny. Very unlike today, when it is snowing here in the high country.

You know, if we can put together a tour of Civil War sites here in little old Avery County that covers an entire afternoon, imagine what kind of tour we could do in a place that has a lot more Civil War history...

Next on our adventure was the Montezuma Community Cemetery. William McKeeson "Keith" Blalock, and his wife, Sarah Malinda Pritchard "Sam" Blalock are buried here. Keith and Sam both served in the 26th North Carolina. There are other Civil War vets buried here as well - six total.

Our last stop for the afternoon was the property known as Grasslands - the home of Col. John B. Palmer during the war. Palmer moved here in 1858, and in 1864, on his way back from his Camp Vance raid, Kirk ordered, or at least sanctioned, the burning of Palmer’s house.

We talked about a couple of other sites as well - the Cranberry mines, which produced iron ore during the war. The iron ore was shipped off the mountain by wagon loads to the railroad just west of Morganton. We also discussed the underground railroad that the Blalocks helped run: an underground railroad that helped funnel escaped prisoners from Salisbury to east Tennessee. The Blalocks ran the Blowing Rock-Shull’s Mill-Banner Elk portions (then all in Watauga County) of the line.

Overall it was a great afternoon - the weather was good - a little cool, but sunny. Very unlike today, when it is snowing here in the high country.

You know, if we can put together a tour of Civil War sites here in little old Avery County that covers an entire afternoon, imagine what kind of tour we could do in a place that has a lot more Civil War history...

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

CW Sites in Western NC, part 3

Civil War sites in western North Carolina, part 3

Part 1 of this topic looked at sites along the Blue Ridge, part 2 along the I-26 corridor, and this final part will look at sites west of Asheville.

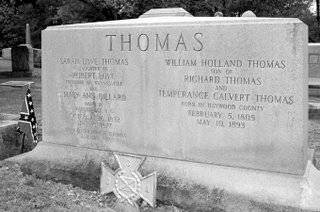

While there were a number of small actions in far-western North Carolina, there are not many sites. Anyone in this area should visit the Museum of Cherokee Indians in Cherokee, on the North Carolina side of the Great Smokey Mountain National Park. There is information here (an exhibit) on Thomas’s Legion, along with the Legion’s original battle flag. There is also a Confederate monument in Cherokee dedicated "in Honor of those brave Cherokee Indians Loyal to the Confederacy... Commanded by Wm. H. Thomas."

While on the subject of Thomas, his grave is in the Green Hill Cemetery in Waynesville. There are quite a few other Confederate graves in this cemetery. Waynesville is hailed as the site of the "last skirmish of the War Between States." There is a monument near old White Sulphur Springs that reads "Near this spot was fired the last shot of the War Between the States, under the command of Lt. Robert T. Conley, of the Confederate Army, May 6, 1865." The monument was erected by the UDC.

There are other sites in the area, like the Old Mother Cemetery in Robbinsville, where Brig. Gen. John W. McElroy is buried. There is also a Confederate monument in Franklin.

A piece of advice - call some of these place before you visit. Many museums here in western North Carolina close in the winter time, or operate on a limited schedule.

Friday, November 10, 2006

CW Sites in Western NC, part 2

Civil War sites in Western North Carolina continued....

The I-26 corridor has several good Civil War sites. In between Flat Rock and Hendersonville is Connemara, the home of Confederate Secretary of the Treasury Christopher Memminger. Memminger had the house constructed in 1938. Connemara is probably better known as the home of Carl Sandburg, who purchased the property in 1945. Sandburg won a Pulitzer for his four- volume biography of Abraham Lincoln. The site is now owned by the National Park Service and is open for tours. Nearby is the St. Johns of the Wilderness Episcopal Church, which has both the grave of Memminger and of Lt. Col. Charles de Choisel of the 7th Louisiana Infantry, or Wheat’s Tigers. This tiered cemetery has got to be the best cemetery in western North Carolina.

While in the area, check out the 1855 Woodfin Inn, now a bed and breakfast.

A little further north, up US 26 in Fletcher, is the Open Air Westminster Abbey of the South, located behind the Cavalry Episcopal Church. On the grounds are monuments to R. E. Lee, Dan Emmett, Stephen Foster, O. Henry, and Albert Pike, among others.

If you continue north, you will come to Asheville. The best place to visit in the city is the cemetery, Riverside. North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance, former colonel of the 26th NC, is buried in the cemetery, along with his brother, Brig. Gen. Robert B. Vance (former colonel of the 29th NC). Thomas L. Clingman and James G. Martin are two other Confederate generals buried in the cemetery. There are numerous other Confederates buried within the cemetery, and at least one Federal soldier,

There are breastworks, almost unrecognizable, on the campus of UNC-Asheville at the Botanical Gardens.

Also close to Asheville, off the Blue Ridge Parkway, is Soco Gap. Soco can mean either "ambush place" or "where the Spaniard is thrown in the water." A skirmish was fought hear between Kirk (Union) and Thomas’s Legion (Confederate).

Still further north is the Vance Birthplace State Park, off Reams Creek Road. These are the actual cabins in which Vance grew up.

A little further north, into Madison County, is the site of the Shelton Laurel Massacre. The County was called "Bloody Madison" at the start of the war and there is a book entitled Victims about the tragic events that took place there.

More to come.....

The I-26 corridor has several good Civil War sites. In between Flat Rock and Hendersonville is Connemara, the home of Confederate Secretary of the Treasury Christopher Memminger. Memminger had the house constructed in 1938. Connemara is probably better known as the home of Carl Sandburg, who purchased the property in 1945. Sandburg won a Pulitzer for his four- volume biography of Abraham Lincoln. The site is now owned by the National Park Service and is open for tours. Nearby is the St. Johns of the Wilderness Episcopal Church, which has both the grave of Memminger and of Lt. Col. Charles de Choisel of the 7th Louisiana Infantry, or Wheat’s Tigers. This tiered cemetery has got to be the best cemetery in western North Carolina.

While in the area, check out the 1855 Woodfin Inn, now a bed and breakfast.

A little further north, up US 26 in Fletcher, is the Open Air Westminster Abbey of the South, located behind the Cavalry Episcopal Church. On the grounds are monuments to R. E. Lee, Dan Emmett, Stephen Foster, O. Henry, and Albert Pike, among others.

If you continue north, you will come to Asheville. The best place to visit in the city is the cemetery, Riverside. North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance, former colonel of the 26th NC, is buried in the cemetery, along with his brother, Brig. Gen. Robert B. Vance (former colonel of the 29th NC). Thomas L. Clingman and James G. Martin are two other Confederate generals buried in the cemetery. There are numerous other Confederates buried within the cemetery, and at least one Federal soldier,

There are breastworks, almost unrecognizable, on the campus of UNC-Asheville at the Botanical Gardens.

Also close to Asheville, off the Blue Ridge Parkway, is Soco Gap. Soco can mean either "ambush place" or "where the Spaniard is thrown in the water." A skirmish was fought hear between Kirk (Union) and Thomas’s Legion (Confederate).

Still further north is the Vance Birthplace State Park, off Reams Creek Road. These are the actual cabins in which Vance grew up.

A little further north, into Madison County, is the site of the Shelton Laurel Massacre. The County was called "Bloody Madison" at the start of the war and there is a book entitled Victims about the tragic events that took place there.

More to come.....

Friday, November 03, 2006

CW sites in western North Carolina, part 1

Mike Ables, from Apopka, Fl (by the way - did you know that your hometown newspaper was started by a Confederate veteran from North Carolina?) recently wrote asking about Civil War sites in western North Carolina. There are not many. While George Stoneman did come through with a sizeable force of Federal cavalry in March 1865, which did result in several minor skirmishes, there were no large-scale pitched battles in the area. There are also no battlefield parks. But there are a few sites in western north Carolina worth checking out.

Fort Defiance, in Caldwell County, was built by the Lenoirs in the late 1700s. It was visited by Stoneman. While Stoneman's men burned many structures, Fort Defiance was saved. It has been restored, and is well worth the visit. While also in Caldwell County, visit the Caldwell Historical Museum in downtown Lenoir. It is a wonderful museum and has some good information about the War.

In Burnsville, in Yancey County, you will find the Rush-Wray Museum of Yancey County History. It is located in the ca. 1840 McElroy House. McElroy was a pre-war militia colonel, and in the summer of 1863, became brigadier general of the first brigade of North Carolina Home Guard. It is believed that he used this structure as his headquarters while he was in Burnsville. It is also believed that the house was used as a hospital after a skirmish in the town in April 1864. McElroy's daughter, Harriett, married Brig. Gen. Robert Vance, and McElroy's son, John S. McElroy, was colonel of the 16th NCT.

The Avery County Historical Museum in Newland also has a small Civil War display. A few miles from Newland (towards Linville) are the graves of Keith (McKeesan) and Malinda (Sam) Blalock, one-time members of the 26th NCT, and later Unionists who operated an underground railroad for escaped Union prisoners in western North Carolina. Their graves are in the Montezuma Community Cemetery.

While in the area, don't forget to visit the Carson House, just west of Marion, in McDowell County. The home, constructed in 1793, survived a burning attempted in the last days of the war.

More to come....

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Robnett and Key familes, battle of Hanover Court House - October 23, 2006

Most folks in North Carolina who are interested in the war have heard of the Robnett brothers. There were four brothers, all from Alexander County, who served in Company G of the 37th North Carolina Troops. All enlisted on October 9, 1861. Three of the four-- Joel, John, and William-- were killed on May 27, 1862, at the battle of Hanover Court House, Virginia.

A lesser known story is that of the Key family of Surry County. On May 4, 1861, two weeks before North Carolina voted to leave the Union, the Surry Regulators were organized in Surry County. Richard E. Reeves was elected Captain. On September 21, 1861, the Regulators became Company A of the 28th North Carolina Troops. Marvin V. Key was one of those original volunteers who enlisted in May 4. He was 18 years old.

Company A received an influx of new recruits in March 1862. They included Marvin’s brother James, age 26, and a cousin, R. J. Key. James was married and had two small children at home. Nothing else is known about R. J. Another brother, Andrew J., would join the regiment (at the age of 17) in October 1864. James and R. J. made their way to the regiment, then stationed around Kinston. There would be six men with the Key surname in Company A.

In early May 1862, the 28th North Carolina, along with the other regiments of Branch’s brigade, was transferred to Gordonsville, Virginia. Later that month, the brigade was moved to Hanover Court House. On May 27, 1862, Federal commander George B. McClellan decided to clear out the Confederates in Hanover County, opening the way for Irvin B. McDowell’s First Corps, at Fredericksburg, to rejoin the rest of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan chose Fitz John Porter’s Fifth Corps for the job.

About mid-morning on May 27, 1862, General Branch learned that a group of Federals was crossing the Pamukey River near Hanovertown. Branch, believing the Federal party to be small in number, sent the 28th North Carolina to reinforce the pickets he had posted the night before and to captured this small party of Federals. When the 28th North Carolina got into position, the men discovered the Federals were coming up the road they had just crossed. The regiment reversed itself and slammed into the 25th New York, killing many and taking 70 prisoners. The 28th North Carolina was then attacked by Dan Butterfield’s brigade and forced to retreat. Somewhere during the action, probably around the Kinney Farm House, Marvin, James, and their cousins R. J., were killed.

Neither the bodies of the Robnett family, nor of the Key family, were ever identified. They were buried on the field, and later, most likely, removed to Hollywood Cemetery after the war.

So not only did sad news go to the Robnett family in Alexander County, but also to the Key family in Surry County.

A lesser known story is that of the Key family of Surry County. On May 4, 1861, two weeks before North Carolina voted to leave the Union, the Surry Regulators were organized in Surry County. Richard E. Reeves was elected Captain. On September 21, 1861, the Regulators became Company A of the 28th North Carolina Troops. Marvin V. Key was one of those original volunteers who enlisted in May 4. He was 18 years old.

Company A received an influx of new recruits in March 1862. They included Marvin’s brother James, age 26, and a cousin, R. J. Key. James was married and had two small children at home. Nothing else is known about R. J. Another brother, Andrew J., would join the regiment (at the age of 17) in October 1864. James and R. J. made their way to the regiment, then stationed around Kinston. There would be six men with the Key surname in Company A.

In early May 1862, the 28th North Carolina, along with the other regiments of Branch’s brigade, was transferred to Gordonsville, Virginia. Later that month, the brigade was moved to Hanover Court House. On May 27, 1862, Federal commander George B. McClellan decided to clear out the Confederates in Hanover County, opening the way for Irvin B. McDowell’s First Corps, at Fredericksburg, to rejoin the rest of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan chose Fitz John Porter’s Fifth Corps for the job.

About mid-morning on May 27, 1862, General Branch learned that a group of Federals was crossing the Pamukey River near Hanovertown. Branch, believing the Federal party to be small in number, sent the 28th North Carolina to reinforce the pickets he had posted the night before and to captured this small party of Federals. When the 28th North Carolina got into position, the men discovered the Federals were coming up the road they had just crossed. The regiment reversed itself and slammed into the 25th New York, killing many and taking 70 prisoners. The 28th North Carolina was then attacked by Dan Butterfield’s brigade and forced to retreat. Somewhere during the action, probably around the Kinney Farm House, Marvin, James, and their cousins R. J., were killed.

Neither the bodies of the Robnett family, nor of the Key family, were ever identified. They were buried on the field, and later, most likely, removed to Hollywood Cemetery after the war.

So not only did sad news go to the Robnett family in Alexander County, but also to the Key family in Surry County.

US 70 - October 18, 2006

This past weekend, I was in Morehead City for the 65th Annual Awards Banquet of the North Carolina Society of Historians. The Society honored me with two of their Willie Parker Peace History Book Awards. Those two books are A Short History of Old Watauga County and The Battle of Hanover Court House: Turning Point of the Peninsula Campaign. It was a great honor and I would publically like to thank NCSH for the awards.

I spent some time visiting some of the historical sites in the area, namely, the old Beauford Burial Grounds, the North Carolina Maritime Museum, and Fort Macon.

On the way home, I came to this conclusion: no section of North Carolina is more steeped in Civil War history than that US 70 corridor. Fort Macon was first taken by state forces on April 14, 1861. The area remained under Confederate control for almost a year. New Bern was lost in battle on March 14, 1862. Havelock Station, Carolina City, Morehead City, and Beaufort were all under Union control by March 24. A month later, Fort Macon was bombarded and surrendered the same evening.

Twice during the war, Federal-controlled New Bern was attacked by Confederate forces. The first was in March 1863 when D. H. Hill launched a three-pronged attack against the city which failed. In February 1864, 13,000 soldiers from the Army of Northern Virginia attacked the city and once again were forced back.

Then there is Foster’s raid, led by Union General John G. Foster. The raid started in New Bern on December 11, 1862. On December 14, a small skirmish was fought at Southwest Creek, below Kinston, followed by an attack at Kinston itself. This was followed by skirmishing at Whitehall, now known as Seven Springs. But Foster’s force was turned back on December 17, during a battle just south of the town of Goldsboro.

War came again during the first months of 1865. At Southwest Creek, about five miles east of Kinston, the two forces clashed again on March 7, and on March 10. The Confederates were at first successful, but were forced to retreat when the Federals were reenforced. This battle is known as the second battle of Kinston, the battle of Southwest Creek, or the battle of Wise’s Forks. One historian believes it to be the second largest land battle in North Carolina during the war. On March 12, the ironclad CSS Neuse was sunk in the Neuse River. Goldsboro was peacefully occupied by Federal soldiers from Gen. Sherman’s army that same month.

Bentonville Battlefield is not far off US 70, not far from Goldsboro. If you were to continue west on US 70, you would eventually come to Raleigh.

Once again, I contend that the land around modern US 70, from the coast back towards Raleigh, saw more action during the war than any other point in North Carolina.

I spent some time visiting some of the historical sites in the area, namely, the old Beauford Burial Grounds, the North Carolina Maritime Museum, and Fort Macon.

On the way home, I came to this conclusion: no section of North Carolina is more steeped in Civil War history than that US 70 corridor. Fort Macon was first taken by state forces on April 14, 1861. The area remained under Confederate control for almost a year. New Bern was lost in battle on March 14, 1862. Havelock Station, Carolina City, Morehead City, and Beaufort were all under Union control by March 24. A month later, Fort Macon was bombarded and surrendered the same evening.

Twice during the war, Federal-controlled New Bern was attacked by Confederate forces. The first was in March 1863 when D. H. Hill launched a three-pronged attack against the city which failed. In February 1864, 13,000 soldiers from the Army of Northern Virginia attacked the city and once again were forced back.

Then there is Foster’s raid, led by Union General John G. Foster. The raid started in New Bern on December 11, 1862. On December 14, a small skirmish was fought at Southwest Creek, below Kinston, followed by an attack at Kinston itself. This was followed by skirmishing at Whitehall, now known as Seven Springs. But Foster’s force was turned back on December 17, during a battle just south of the town of Goldsboro.

War came again during the first months of 1865. At Southwest Creek, about five miles east of Kinston, the two forces clashed again on March 7, and on March 10. The Confederates were at first successful, but were forced to retreat when the Federals were reenforced. This battle is known as the second battle of Kinston, the battle of Southwest Creek, or the battle of Wise’s Forks. One historian believes it to be the second largest land battle in North Carolina during the war. On March 12, the ironclad CSS Neuse was sunk in the Neuse River. Goldsboro was peacefully occupied by Federal soldiers from Gen. Sherman’s army that same month.

Bentonville Battlefield is not far off US 70, not far from Goldsboro. If you were to continue west on US 70, you would eventually come to Raleigh.

Once again, I contend that the land around modern US 70, from the coast back towards Raleigh, saw more action during the war than any other point in North Carolina.

The Cousins brothers - October 12, 2006

For the past couple of days I’ve been working on an article about Franklin and William Henry Cousins. Both served in the 37th North Carolina Troops and both were tri-racial: African-American, Native-American, and white, commonly known today as Melugeon.

They were from Randolph County, North Carolina, and came to Watauga County sometime around 1850. In 1860, Franklin was married and William Henry still lived at home. When then- Capt. George N. Folk formed the Watauga Rangers in May 1861, he took both men and impressed them into service as company servants. Mark Holesclaw, also from Watauga, wrote a letter to Governor Ellis asking that the two be set free. They were, and in September 1861, both volunteered to serve in the Watauga Marksmen, which would become Company B, 37th North Carolina Troops. William Henry became the regimental wagoner, a common occupation for free persons of color in the Southern army. But Franklin maintained his place on the front lines, and was killed at the battle of Second Manassas on August 29, 1862. His remains lie in a unknown grave. I wonder what ever become of his widow Elizabeth and his daughter Mary?

For most of my life, I have been interested in the common soldier. For the years that I actively served as a living historians/reenactor/interpreter, I worked to teach people about those who lived in the 1860s. I still do that today, but less with rifle or sword in hand, and more with a keyboard. How many other stories are there out there like the story of the Cousins brothers? I hope to find those stories that, if not recorded, will be lost.

Hopefully the article on the Cousins brothers will find a home. When our ancestors are portrayed as an all-white, all-slave owning aristocracy, it is not easy to swim upstream. But that Hollywood image of a homogenous Confederate Army does a grave disservice to brave and fascinating men like Franklin and William Henry.

They were from Randolph County, North Carolina, and came to Watauga County sometime around 1850. In 1860, Franklin was married and William Henry still lived at home. When then- Capt. George N. Folk formed the Watauga Rangers in May 1861, he took both men and impressed them into service as company servants. Mark Holesclaw, also from Watauga, wrote a letter to Governor Ellis asking that the two be set free. They were, and in September 1861, both volunteered to serve in the Watauga Marksmen, which would become Company B, 37th North Carolina Troops. William Henry became the regimental wagoner, a common occupation for free persons of color in the Southern army. But Franklin maintained his place on the front lines, and was killed at the battle of Second Manassas on August 29, 1862. His remains lie in a unknown grave. I wonder what ever become of his widow Elizabeth and his daughter Mary?

For most of my life, I have been interested in the common soldier. For the years that I actively served as a living historians/reenactor/interpreter, I worked to teach people about those who lived in the 1860s. I still do that today, but less with rifle or sword in hand, and more with a keyboard. How many other stories are there out there like the story of the Cousins brothers? I hope to find those stories that, if not recorded, will be lost.

Hopefully the article on the Cousins brothers will find a home. When our ancestors are portrayed as an all-white, all-slave owning aristocracy, it is not easy to swim upstream. But that Hollywood image of a homogenous Confederate Army does a grave disservice to brave and fascinating men like Franklin and William Henry.

Getting Started - October 11, 2006

A blog about North Carolina’s role in the Second American Revolution? Why not? North Carolina’s role in the late unpleasantries is often understated and less often written about. Why do we have 70+ Confederate regiments from North Carolina, and only a half dozen modern regimental histories?

I did not grow up in North Carolina, but I have ancestors who first settled in the state (Wilkes County) in 1771. I have Confederate ancestors in eight different Confederates states. I have lived in the Tar Heel State since 1995.

I’ve also been writing about North Carolina’s role in the War for the past ten years, and I don’t plan to stop anytime soon. Some of my published writings have focused on Brig. Gen. Collet Leventhorpe, the role of different individuals from North Carolina at Gettysburg, the 37th North Carolina Troops (book and articles), the Battle of Hanover Court House, Virginia, and Veterans and Reunions in North Carolina after the war. I’ve also written some local history (Watauga, Avery, Caldwell, and Yancey counties).

Currently, I am working on a book about the 58th North Carolina Troops, one of the orphaned North Carolina regiments. The 58th North Carolina was sent west and became part of the Army of Tennessee.

The purpose of this blog is to explore North Carolina’s role during the Civil War: the people, the places, the regiments, the battles. These writings will often deal with just the period of time around the war, even though I might occasionally slip into modern events that involve that time period of history. I hope to update a couple of times a week.

If you would like to know more about me, and my books, please check out my web page: www.michaelchardy.com And, do me a favor, tell everyone you know about this blog.

I did not grow up in North Carolina, but I have ancestors who first settled in the state (Wilkes County) in 1771. I have Confederate ancestors in eight different Confederates states. I have lived in the Tar Heel State since 1995.

I’ve also been writing about North Carolina’s role in the War for the past ten years, and I don’t plan to stop anytime soon. Some of my published writings have focused on Brig. Gen. Collet Leventhorpe, the role of different individuals from North Carolina at Gettysburg, the 37th North Carolina Troops (book and articles), the Battle of Hanover Court House, Virginia, and Veterans and Reunions in North Carolina after the war. I’ve also written some local history (Watauga, Avery, Caldwell, and Yancey counties).

Currently, I am working on a book about the 58th North Carolina Troops, one of the orphaned North Carolina regiments. The 58th North Carolina was sent west and became part of the Army of Tennessee.

The purpose of this blog is to explore North Carolina’s role during the Civil War: the people, the places, the regiments, the battles. These writings will often deal with just the period of time around the war, even though I might occasionally slip into modern events that involve that time period of history. I hope to update a couple of times a week.

If you would like to know more about me, and my books, please check out my web page: www.michaelchardy.com And, do me a favor, tell everyone you know about this blog.